Atrial Fibrillation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia among patients with aortic stenosis and portends an increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes whether or not surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is performed. AF and aortic stenosis share multiple common risk factors, such as advanced age and hypertension, and the valvular disease itself may predispose to AF (from increased left atrial pressure and enlargement, leading to atrial fibrosis and regional conduction abnormalities). Pre-existing AF is a well-established predictor of mortality after SAVR, with an 8-fold increase in the risk of late mortality compared with patients without AF. A consistent finding was described among patients with chronic AF undergoing TAVR, where AF emerged as an independent predictor of late mortality, with a 1.7-fold increase in the risk of all-cause death and a 2.1-fold increase in the risk of cardiovascular death. In particular, TAVR patients with pre-existing AF experience an increased risk of death irrespective of the type of AF: permanent (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.47; 95% CI: 1.40-4.38; P = 0.002), persistent (HR: 3.60; 95% CI: 1.10-11.78; P = 0.034), or paroxysmal (HR: 2.88; 95% CI: 1.37-6.05; P = 0.005). Moreover, Okuno et al in a recent study confirmed that both nonvalvular and valvular AF in patients undergoing TAVR were associated with a 1.8-fold and 3.2-fold increase in the risk of cardiovascular death or disabling stroke.

Conversely, the precise prevalence, risk factors and prognostic impact of new-onset AF, a frequent complication following SAVR or TAVR, have not yet been fully clarified. In the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) cohort A, the prevalence of preoperative AF was similar between treatment groups (40.8% TAVR group vs 42.7% SAVR group), whereas the incidence of new-onset AF in patients undergoing TAVR was lower (TAVR 8.6% vs SAVR 16%; P = 0.006), with a shorter duration. This is because perioperative myocardial injury and the magnitude of systemic inflammatory response is likely higher after SAVR than TAVR procedures. Consistent with these findings, other trials and multicenter studies reported a frequency of new-onset AF after TAVR ranging from 6.8% to 8.8%. Only a few, small studies have assessed the clinical impact of new-onset AF after TAVR and have reported conflicting results. A meta-analysis of 14,078 patients found that only pre-existing AF, but not new-onset AF, was associated with increased late mortality. On the contrary, more recent studies have shown a significant increase rate in early and late mortality for patients with new-onset AF compared with patients with no AF.

Interestingly, the most recent studies report that new-onset AF carries a significantly worse prognosis and is associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality (relative risk [RR]: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.26 to 1.45; P < 0.001), stroke (RR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.63 to 2.26; P < 0.01), bleeding (RR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.48 to 1.86; P < 0.01), and heart failure hospitalization (RR: 1.98; 95% CI: 1.81 to 2.16; P < 0.01) compared with patients with pre-existing AF.

In this issue of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, Ryan et al add new light on this matter through a comprehensive, systematic review and meta-analysis of 179 studies evaluating a cohort of 241,712 patients (and excluding 55,271 patients with pre-existing AF). In line with most previous studies, new-onset AF occurred in approximately 1 in 10 TAVR patients with an overall occurrence of 9.9% (95% CI: 8.1%-12.0%). This arrhythmia was associated with several adverse outcomes, including mortality (RR: 1.8; 95% CI: 1.1-2.8; P < 0.0001), stroke (RR: 1.8; 95% CI: 1.2-2.5; P = 0.002), major bleeding (RR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4-1.8; P < 0.0001), permanent pacemaker implantation (RR: 1.1; 95% CI: 1.1-1.2; P = 0.0002), and longer hospitalization (mean difference 2.7 days, 95% CI: 1.1-4.3 days; P = 0.00001). A clear pathophysiologic mechanism explaining why new-onset AF after TAVR is associated with worse outcomes is not certain. This relationship, the investigators believe, is probably multifactorial, and includes hemodynamic and functional impairment, which in turn is associated with increased risk of thromboembolic and bleeding events. The abrupt loss of atrioventricular synchrony leads to an acute impaired ventricular filling, reduced cardiac output, and increased afterload, which adversely affect clinical outcomes among heart failure patients. Moreover, TAVR patients with both pre-existing or new-onset AF also have a higher incidence of conduction disturbances and bradyarrhythmias requiring permanent pacemaker implantation. Despite all this, it is remarkable that AF status is not included in the available TAVR risk scores.

Related to the development of new-onset AF, the investigators identified a number of clinical risk factors such as older age (mean difference 1.6 years, 95% CI: 1.1-2.0 years; P < 0.0001), chronic kidney disease (1.2, 95% CI: 1.1-1.3; P = 0.002), peripheral vascular disease (RR: 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1-1.6; P = 0.01), severe mitral regurgitation (RR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.5-3.6; P = 0.0002), pulmonary hypertension (RR: 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1-1.6; P = 0.01), and higher Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score (mean difference 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2-0.6; P = 0.0003). Regarding procedural factors, transapical access was associated with a significantly higher rate of new-onset AF, as previously reported, but this route is rarely used in current clinical practice. New-onset AF after TAVR occurs more frequently in elderly patients with a high burden of comorbidities that predispose them to postprocedural arrhythmias. This suggests that new-onset AF is likely due to a combination of patient substrate and procedure-related factors, including postoperative inflammation, enhanced sympathetic stimulation, and oxidative stress. However, clinical risk factors such as age and other co-morbidities must be reconsidered in the context of the evolution of TAVR, expanding to lower-risk and younger patients. Recently, Mentias et al noted a steady decline in the occurrence of new-onset AF in the 3 years of the study period in patients undergoing non-transapical TAVR: the incidence decreased from 6.8% in 2014 to 4.9% in 2016. Results from PARTNER 3 reaffirm that early postoperative AF remains a common phenomenon following SAVR, occurring in 36.6% of patients, whereas after TAVR, it was even more infrequent (4.3%) as compared with previous trials due to the lower-risk population enrolled.

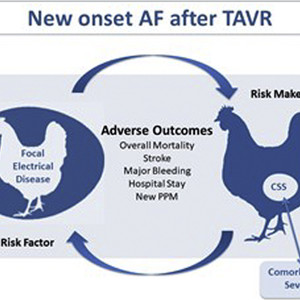

In this context, a fundamental question needs to be asked. Is it possible that new-onset AF after TAVR is a marker of overall clinical fragility rather than a risk factor for adverse events? If new-onset AF is a direct cause of mortality, stroke, and bleeding, then focused arrhythmia treatment with restoration of sinus rhythm should seemingly reduce the risk of adverse outcomes. Conversely, if new-onset AF is a marker of comorbid state severity, then treatment of AF would be like treating an infection with antipyretics. Nevertheless, treatment of new-onset AF is always warranted, because unaddressed AF causes adverse outcomes. Taken together, patients who develop new-onset AF after TAVR are more “ hemodynamically frail” and may also represent a sicker patient cohort with worse systemic insult at higher risk of complications after the procedure. The combination of both conditions leads to higher mortality and worse outcome (Figure 1).

New-Onset AF Mechanistic Paradox

Due to their multiple comorbidities, TAVR patients are likely to be at a high thromboembolic as well as bleeding risk, making appropriate management of AF challenging. In the PARTNER 3 (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial, <50% of patients with both early and late postoperative AF were on anticoagulant therapy. Furthermore, by hospital discharge, early new-onset AF after TAVR resolved in 83% of cases. The underuse of antithrombotic therapy for new-onset AF is likely multifactorial, including the common view of early AF as a self-limited phenomenon and the difficult balance between bleeding and embolic risk in elderly patients. Unfortunately, in this meta-analysis, the investigators were unable to evaluate whether antithrombotic therapy might modify the increased stroke risk. A further limitation is the lack of time-course assessment of post-operative AF. In the PARTNER 3 trial, late (post-discharge) AF, but not early postoperative AF, was significantly associated with worse outcomes at 2 years in this low-risk population, irrespective of treatment modality (SAVR or TAVR). Promising preliminary results have been obtained on the clinical impact of ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring post-TAVR, with significant therapeutic changes, reporting a prevalence of new-onset AF after discharge ranging from 2.6% to 10.5%. This finding suggests that vigilant cardiac rhythm monitoring and frequent clinical evaluation for several months following the index procedure is crucial. Another important limitation of most studies is the absence of a consistent temporal correlation of new-onset AF and adverse events. Ryan et al were not able to collect patient-level data to analyze the timeline of events to confirm that new-onset AF always preceded the supposedly associated adverse outcomes. In summary, as TAVR procedures are more frequently performed in younger and lower-risk populations, a strategy aimed at in-hospital and ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring after the procedure with prompt identification of new-onset AF followed by an appropriate treatment seems mandatory to optimize outcomes.

This article is reproduced from JACC journals.

surgerycast

Shanghai Headquarter

Address: Room 201, 2121 Hongmei South Road, Minhang District, Shanghai

Tel: 400-888-5088

Email:surgerycast@qtct.com.cn

Beijing Office

Address: room 709, No.8, Qihang international phase III, No.16, Chenguang East Road, Fangshan District, Beijing

contact number:13331082638(Liu Jie)