Aortic Valve Replacement and Patient-Centered Implementation: To Boldly Go Where No Device Has Gone Before

Over the past 10 years, we have witnessed the unprecedented and rapid revolution of aortic valve replacement (AVR) due to the introduction of a disruptive technology—transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Supported by expertly conducted landmark clinical trials by multiple device manufacturers, the speed with which care for severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) has been transformed has been astonishing. The approval of TAVR in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration started with prohibitive surgical risk patients in November 2011 and progressed to approvals for high-risk patients in 2014, TAVR valve-in-valve in 2015, intermediate-risk patients in 2016, and approval for low-risk patients in 2019. The scientific evidence supporting these approvals has been substantial, and the evidence supporting TAVR has markedly improved the clinical science of the management of AS. With each new TAVR indication came substantial shifts in the patterns of care for patients with severe, symptomatic AS. Administrative claims analyses indicated a reduction in isolated surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) volumes, a concurrent decrease in SAVR risk profile, and reductions in SAVR short- and long-term mortality at sites performing TAVR. Additionally, claims analyses indicated SAVR and TAVR outcomes at sites performing both procedures were linked (3). Importantly, as indications for TAVR continued to expand, geographic access to TAVR and the number of sites offering both SAVR and TAVR also grew substantially.

Concurrent to these landmark advances in the commercial availability of TAVR and the sea change in AVR care, TAVR devices and individual care underwent rapid iteration. The design of TAVR valves and their delivery mechanisms have evolved to incorporate a number of important innovations to improve device performance and flatten the learning curve, including: 1) recapturable devices to allow for more precise device placement and reducing valve embolization; 2) sealing skirts to reduce paravalvular leak, which can be associated with heart failure and increased mortality; and 3) reduction of access sheath size to reduce vascular complications and increase the use of transfemoral access. Along with these device design innovations, the last decade has also allowed operators and institutions to gain valuable experience and progress along the operator and institutional learning curves, ostensibly improving the quality of AVR care.

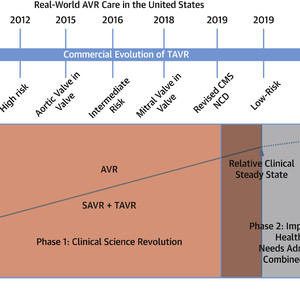

The Evolution of Real-World AVR Care in the United States

The introduction of TAVR created a clinical science revolution that increased the quality of AVR care. With the approval of low-risk TAVR, AVR has entered into an Implementation Science and Health Policy phase. Orange = Phase 1 (Clinical Science Revolution). Gray = Phase 2 (Implementation Science and Health Policy Revolution). AVR = aortic valve replacement; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; NCD = National Coverage Decision; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; STS ACSD = Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery database; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TVTR = Transcatheter Valve Therapies Registry.

Together, the clinical trials in support of the efficacy of TAVR, the engineering innovation in subsequent device iterations, and the associated expansion of commercial TAVR availability have ushered AVR through a period of disruption into a newfound state of maturity. To be fair, some “final clinical frontiers” of AVR care remain, including bicuspid valve disease, adjunctive medical therapy, TAVR-associated pacemaker rates, and the lifetime management of TAVR in younger patients (valve durability, etc). However, the answers to these questions will represent important refinements to the current standards of care rather than transformative leaps and are likely to require pragmatic, low-cost studies to answer.

With this background, in this issue of the Journal, Mori et al undertake an analysis of fee-for-service Medicare administrative claims to understand the totality of AVR care. Specifically, the investigators state that the motivation for their analysis is to address residual gaps in our understanding of AVR after the publication of the latest update on the state of TAVR in the United States which contained little data about SAVR. Using Medicare claims to identify both SAVR and TAVR care from 2012 to 2019, Mori et al demonstrate:

| • | An increase from 107 to 156 AVR/100,000 Medicare beneficiaries; |

| • | A decline in SAVR, from 88 to 54/100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, essentially all due to a decrease in isolated AVR; |

| • | Increase in TAVR from 19 to 101/1,000 Medicare beneficiaries, due in part to indication expansion to intermediate risk during the study period; |

| • | Decrease in 1-year mortality for AVR from 11.9% to 9.4%, with a larger decrease in TAVR than SAVR; |

| • | Decrease in comorbidities among those undergoing AVR, suggesting an overall reduction in patient risk, likely due to the overall expansion in the number of patients undergoing AVR; |

| • | “Will Rogers phenomenon” where age decreased in TAVR and SAVR over time, but overall AVR age increased. There were similar findings for heart failure as a comorbidity decreasing in TAVR and SAVR over time, but increasing in AVR overall. |

Although many of these findings have previously been shown in other Medicare fee-for-service claims analyses, the investigators’ contribution is especially notable for 2 points: 1) their data encompass the period where TAVR indications included prohibitive-, high-, and intermediate-risk patients; and 2) they have shifted the focus from a strict comparison of SAVR and TAVR trends to overall AVR care by demonstrating the Will Rogers phenomenon. This epidemiologic paradox occurs whereby the directionality of trends in the 2 subcomponents of AVR care (SAVR and TAVR) may share 1 directionality, but the trend for overall AVR care is in the opposite direction. The investigators correctly point out that the presence of such a phenomenon in AVR suggests that analyzing SAVR or TAVR in isolation of each other may obscure important truths about the evolution of AVR in the United States.

Though it seems that an inability to fully elucidate trends in overall AVR care by examining SAVR or TAVR alone may represent a relatively minor flaw in our current capabilities for real-world data collection, it is in fact a major public health and health policy problem. In the face of the relative clinical maturity of TAVR, there remain a significant number of societally important public health questions concerning the real-world implementation and provision of AVR care in the United States. The 2020 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Valve Guidelines highlight the following public health issues: 1) identifying and addressing disparities in outcomes and survival across diverse patient populations; 2) development of novel, cost-effective approaches for long-term management in rural settings; and 3) expanding access to therapies for valvular dysfunction. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has acknowledged the issue of access by issuing a revised national coverage decision in 2019 that lowered procedural requirements in an attempt to boost access. However, initial analyses suggest that disparities in geographic access to AVR care will persist and that geographic clustering of TAVR centers may actually reduce the quality of care. Previous analyses of TAVR have also suggested that racial minorities are underrepresented among those receiving TAVR. Lastly, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has been concerned with the quality of TAVR outcomes, and initial validated quality metrics suggest substantial variation in TAVR outcomes by site. It remains to be seen whether simple site feedback of outcomes, as is already done for SAVR and will be done for TAVR, will be sufficient to improve this variation, or whether innovative approaches, such as a combined AVR value-based care model will be needed.

So, if examination of TAVR and SAVR in isolation effectively clouds our ability to recognize simple trends in overall AVR care, as demonstrated by Mori et al how can we hope to solve the complex disparities, implementation, and quality issues that AVR currently face? Mori et al acknowledge that Medicare administrative claims are not the ultimate answer for several reasons: 1) there are a substantial number of patients under the age of 65 years undergoing AVR; 2) fee-for-service Medicare claims do not adequately reflect the growing population of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries; 3) administrative claims have a substantial lag (the Mori et al analysis does not address the era of TAVR approval for low surgical risk patients); and 4) administrative claims alone lack the granularity for rigorous risk adjustment.

Just as TAVR and AVR served as the impetus to pioneer the heart team approach facilitating decision-making for individual patient care, it is time that cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, and their respective professional societies, link the existing STS Adult Cardiac Surgery database and the Transcatheter Valve Therapies Registry, along with administrative claims data. Such a resource would facilitate needed pragmatic, prospective studies and retrospective research to answer pressing implementation and health policy questions specific to this new, mature phase of AVR care in the United States.

This article is reproduced from JACC journals.

surgerycast

Shanghai Headquarter

Address: Room 201, 2121 Hongmei South Road, Minhang District, Shanghai

Tel: 400-888-5088

Email:surgerycast@qtct.com.cn

Beijing Office

Address: room 709, No.8, Qihang international phase III, No.16, Chenguang East Road, Fangshan District, Beijing

contact number:010-5123-5010 13331082638(Liu Jie)