TAVR 20 Years Later: A Story of Disruptive Transformation

Although “innovation” has become the buzzword of the decade, in health care, technological innovation over the last century has been transformative. Without a doubt we are living in what many call the Innovation Age, and the quality of medical care we enjoy today is built on years of effort by some of the world’s best trained and dedicated professionals who continue to work tirelessly to ensure that the medical field maintains its momentum to improve the health and lives of people.

History teaches us that technological advances do not occur overnight. With perseverance, good scientists search for the significance of surprises, coincidences, and sometimes mistakes and turn these into new insights. Author Isaac Asimov once wrote, “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ’Eureka!’ but, ’That’s funny….

When one looks at any truly breakthrough innovation, the myth of a lone genius and a “eureka moment” breaks down. It is never a singular event or achieved by any one person; rather, it is a process in which ideas combine to discover insights that help engineer viable solutions to solve big problems and are then adopted widely to make an impact. It is also a widely held belief that some people are innovators and others are not. The truth is that everyone has a potential role to play: the scientists, engineers, production specialist, and others. For successful disruptive transformation, innovation requires collaboration and is the ultimate team sport.

An example of a transformative technology that has changed the management of severe aortic stenosis patients is transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). The story of TAVR speaks to the power of teamwork and cross collaboration. More importantly it is a testament to how disruptive innovation can forever transform care.

Twenty years ago, Alain Cribier, MD, and colleagues performed the first clinical TAVR procedure in Rouen, France, and the rest we can say is history—history that we have had a front row seat in watching and shaping along the way. Today, TAVR continues to transform the lives of patients with symptomatic heart disease with severe native calcific aortic stenosis (AS) who would have previously been deemed inoperable due to age or other comorbidities.

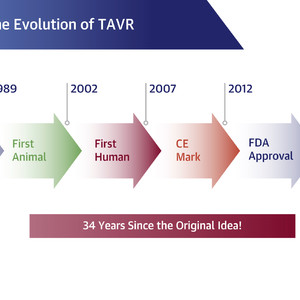

It is important to note that TAVR did not arrive on the scene overnight. Like all scientific endeavors, much work goes into developing, testing, and building upon a hypothesis, with important lessons learned from “failures” and observations along the way (Figure 1). Individuals like Cribier, Henning Rud Andersen, MD, and Martin B. Leon, MD, FACC, spent much of the late 1980s and 1990s working with engineers and others to develop a workable device and solving for challenges ranging from restenosis postprocedure to securing ongoing funding to help move TAVR from concept to reality.

CE = Conformitè Europëenne; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Adapted from Michael Mack, MD, MACC.

Fast forward to 2002, however, and TAVR represented a transformative technology with great potential for treating patients with severe AS. The first TAVR procedure was performed in the United States in 2004 and followed in 2007 by the start of 2, prominent, investigational device exemption randomized trials—the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trials of the balloon-expandable Sapien Valve and the CoreValve/Evolut Trials. These trials, which enrolled >9,600 inoperable patients and showed clear superiority of TAVR to medical therapy, led to initial approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2011 for use in this patient group.

The rollout of TAVR offered a unique opportunity for specialty societies like the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, as well as industry and government agencies, to work together from the very start in ways that had not been done before.

Collaborative stakeholder engagement between cardiologists, surgeons, and other members of the Heart Team is fundamental to the success of TAVR and the high-risk patient population it benefits, so it was only fitting that similar collaborative efforts at the society, government, and industry levels be put in place to guide appropriate use and ensure a measured and data-driven approach to expanding the procedure to broader patient populations.

The 2011 Professional Society Overview from the ACC and STS was among the first guidance and was designed to “set the stage for a series of documents, to be joined by other professional societies, to address the issues critical to successful integration of [TAVR] into medical practice in the United States.” This was followed by the 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS Expert Consensus Document on Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, which focused on successfully implementing TAVR into the flow of patient care based largely on early retrospective studies and registry data. The document specifically addressed early hot topics such as clinical site selection, operator and team training and experience, patient selection and evaluation, procedural performance and complication management, and postprocedural care.

A subsequent 2017 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for TAVR went even further, providing a framework for managing a potential TAVR candidate from the time of patient selection and evaluation to post-TAVR management. Algorithms and check lists that could be easily integrated into electronic health records were also included.

The visionary collaborative endeavor between the ACC and the STS to create the STS/ACC TVT Registry in late 2011 was also an important early effort that played (and continues to play) an important role in postmarket surveillance, hospital reimbursement, the development of clinical guidance, and comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness research. Data from the registry have been invaluable when it comes to providing a comprehensive picture of TAVR procedure volumes, patient characteristics, procedure characteristics, and outcomes over the last 20 years.

Where are we now? Two decades later, we have truly achieved a paradigm shift in managing patients with severe AS. Clinical trials like PARTNER have validated the clinical use of TAVR in a variety of patient populations, including those at intermediate and low risk. According to Michael J. Reardon, MD, FACC, the landmark PARTNER 3 and Evolut trials presented at ACC’s 2019 Annual Scientific Session showing TAVR to be superior or noninferior to surgery in low-risk patients are probably the final trials of the TAVR vs surgery debate. In addition, the recent 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for valvular heart disease provides updated, detailed guidance for transcatheter therapies that take into account the expanded indications for TAVR to all risk groups.

Looking ahead, the TAVR story is not over. Ongoing studies will be focused on long-term outcomes data related to durability and valve deterioration in the younger, low-risk patient population. Additionally, the jury is still out on whether early TAVR intervention in asymptomatic patients could be a possibility, with results from the EARLY TAVR (Evaluation of TAVR Compared to Surveillance for Patients With Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis) trial expected in early 2024. We have also moved on to exploring optimal use of percutaneous interventions for bicuspid aortic valves and aortic regurgitation, as well as mitral and tricuspid valves.

The TAVR odyssey has been driven by the rapid enhancement of technology, a true commitment to collaboration across stakeholders, and a trust and reliance in the scientific process and the constant push to refine and improve—all with the goal of doing what is best for patients. Michael Mack, MD, MACC, sums it up best: “The evolution of TAVR over the past 20 years is truly remarkable. It has truly transformed the treatment of the disease of aortic stenosis. How many times in life have you seen an idea and wished you would have thought of it?”

Author Roy Bennett said, “Don’t be pushed around by the fears in your mind. Be led by the dreams in your heart.” My hope is that we—as a profession and a College—can use the story of TAVR to help us write new stories; that we can be inspired by individuals like Andersen, Cribier, Leon, Holmes, Mack, Webb, and so many others who saw an opportunity to transform care and did not give up on the “crazy idea.” Disruptive innovation is something we should run toward, not away from. Previously, inoperable patients with severe AS had no options. Today they do. That is transformation at its finest.

This article is reproduced from JACC journals.

surgerycast

Shanghai Headquarter

Address: Room 201, 2121 Hongmei South Road, Minhang District, Shanghai

Tel: 400-888-5088

Email:surgerycast@qtct.com.cn

Beijing Office

Address: room 709, No.8, Qihang international phase III, No.16, Chenguang East Road, Fangshan District, Beijing

contact number:13331082638(Liu Jie)